Crime and Motive : Perspectives of a Criminal

To Umar Khalid

“According to the famous jurist Solomon, one should not be punished for his criminal offence if his aim is not against law. If we set aside the motive, then Jesus Christ will appear to be a man responsible for creating disturbances, breaking peace and preaching revolt. But we worship him. Why? Because the inspiration behind his actions was that of a high ideal…”

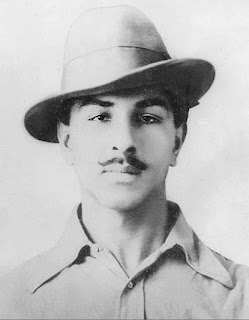

For Bhagat Singh - the orator of the dialogue quoted above - it is the motive of a crime that must be taken into consideration when trying a convict. When most revolutionary groups in India had pinned their hopes on Gandhi’s non-violent struggle, Bhagat Singh's emergence on the national scene towards the end of the 1920s was an exemplary moment of its defiance. In course of time, Singh and his comrades Rajguru and Sukhdev were executed by the state for attempting “to kill or cause injuries to the King Majesty's subjects” and were invariably regarded as dangerous terrorists by the colonial government.

In contrast, Bhagat Singh enjoys immense popularity as a ‘martyr’ among the masses today and is widely embraced as a ‘rebel’ against an oppressive state. Perhaps what marks this change of opinions is the public appearance of his own writings in defence of his acts, bringing to light his intent behind the same. Are we to suppose then, that the particularly negative connotations attributed to the concepts of sedition, conspiracy cases, and most of all ‘terrorism’ in present times, are mere colonial constructs used all the more so in today’s age to depoliticise and dehumanise the actions of groups and individuals against the state, masquerading only as a veil to the actual intent and motive of the ‘acts of terror’ committed? It is this question that I hope to analyse in this paper, primarily through the writings of Bhagat Singh and his comrades themselves.

“Sorry for the death of a man. But in this man has died the representative of an institution which is so cruel, lowly and so base that it must be abolished. In this man has died an agent of the British authority in India - the most tyrannical Government of all Governments in the world.

Sorry for the bloodshed of a human being; but the sacrifice of individuals at the altar of the Revolution that will bring freedom to all and make the exploitation of man by man impossible, is inevitable.”

Thus reads a handwritten leaflet justifying the murder of Assistant Superintendent of Police John P Saunders, written on December 18, 1928 at Mozang House and pasted at several places on the walls of Lahore in the night between 18th and 19th December. A copy in Bhagat Singh's handwriting was produced as an exhibit in the Lahore Conspiracy Case. Singh and his comrades thus, make it very evident that the motive of this murder was not the mere killing of a man, but to demonstrate their protest against the state-endorsed oppression.

In recent times, ‘terrorism’ and ‘national security’ have developed and matured as part of a singular discursive project that continues to undermine the democratic gist of our mass political culture and attempts to replace it with jingoism.i However, this is not a new development and becomes evident when analysing colonial government’s repressive measures in response to the ‘revolutionary’ activities of the HSRA – Hindustan Socialist Republican Association, (previously HRA), of which Bhagat Singh was an active member. Its manifesto, dating back to 1925, spelt out its ideological commitments and tried to condemn the mischievous propaganda against the revolutionaries for being terrorists and anarchists. It reads:

The Indian revolutionaries are neither terrorists nor anarchists: They never aim at spreading anarchy in the land, and therefore they can never properly be called anarchists. Terrorism is never their object and they cannot be called terrorists .... The present Government solely exists because the foreigners have successfully been able to terrorise the Indian people.

And goes on to say:

This official terrorism is surely to be met by counter terrorism .... Moreover the English masters and their hired lackeys can never be allowed to do whatever they like, unhampered, unmolested. Every possible difficulty and resistance must be thrown in their way.

As such, the colonial state did in fact, persistently attempt to create a fictional realm of politics and ‘rule of law’ in order to control the population and stabilise its own sovereignty. By means of these fictions it attempted to establish its monopoly over armed or other forms of violence, and abolish the materiality of terror in the realm of politics. But on various occasions in history, ‘violence’ in the hands of the people threatened to illuminate the real realm of the political and expose the fictional ‘juridical order’. It thus seems possible that the colonial state only invented these various ‘exceptional’ concepts like sedition, conspiracy cases, martial law and, not the least, ‘terrorism’ in order to depoliticise groups and individuals.

It also seems plausible that the the British received unexpected co-operation from elite nationalist politics in their attempt to depoliticise the activities of the anti-colonial revolutionaries, but the latter were resilient in defying all such attempts. In the Congress's endeavours to dominate the Nationalist Movement and their ambition to emerge as the sole spokespersons of the masses, they targeted the militant nationalists for their ‘illegitimate’ strategy of armed violence. Bhagat Singh, disillusioned by Gandhi's dogmatic adherence to non-violence and his withdrawal of the movement turned to militant nationalism. Gandhi decried them as ‘deluded patriots’ and ‘men past reason'.

Because non-violent methods have dominated Western views of the movement for India's independence, many believe that India achieved its freedom without resorting to violence. But violent resistance was in fact, preached and practiced throughout the independence movement and had a significant effect on its course and outcome. Having realised this, when in 1931, the Congress assembly passed a resolution commending the bravery of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru who had been executed for their part in the assassination of the British police officer, the wording of the resolution became a bone of contention between Gandhi's group, which insisted on including a phrase dissociating the Congress from “political violence in any shape or form,” and an anti-Gandhi faction that opposed this disclaimer.

On the other hand, Bhagat Singh was a staunch opponent of the “non-violence” preached by Gandhi. He writes:

"It was the principles of non-violence and compromising policy of Gandhi which created a breach in the united waves that arose at the time of the national movement."

For him, Gandhi's doctrine, which was nothing but a trap to hold back workers and peasants from taking the offensive against the property and rule of capitalists, was at direct odds with what he advocated. Singh writes:

"What is the motive of Congress? I said that the present movement will end in some sort of compromise or total failure. I have said so because in my opinion the real revolutionary forces have not been invited to join the movement. The real armies of the revolution are in villages and factories ‑ the peasants and workers. But our bourgeois leaders don't dare take them along, nor can they do so. These sleeping tigers, once they wake up from their slumber, are not going to stop even after the accomplishment of the mission of our leaders."

Singh brought forward vivid explanations enriching the revolutionary theory and experience of his time. He supported and justified the use of revolutionary violence and his writings proved to be a befitting reply to the meek and virtually servile positions of Gandhi and his followers inside the Congress.

The chain of Bhagat Singh’s relentless resistance of British oppression started with the death of Lala Lajpat Rai who succumbed to the injuries he suffered at the hand of British police in a protest against the Simon Commission. Bhagat Singh planned to kill the Superintendent of Police who ordered the lathi-charge at the protestors to ‘avenge Lala Lajpat Rai’s death’. However, Singh and his associates ended up mistakenly killing the Assistant Superintendent of Police – JP Saunders and went into hiding. In March 1929, Singh resurfaced to protest the formulation of the Defence of India Act, the repressive Public Safety Bill and Trades Dispute Bill and the arrest of 31 labour leaders, and along with his comrade Batukeshwar Dutt, he bombed the assembly premises where the ordinance was in motion. The blast was not meant to harm anyone but only to further the revolution, and both Bhagath Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt surrendered later.

The leaflet thrown in the Central Assembly Hall, New Delhi at the time of the aforementioned bombing read -

"It takes a loud voice to make the deaf hear, with these immortal words uttered on a similar occasion by Valiant, a French anarchist martyr, do we strongly justify this action of ours. In these extremely provocative circumstances, the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association, in all seriousness, realizing their full responsibility, had decided and ordered its army to do this particular action, so that a stop be put to this humiliating farce.

Let the representatives of the people return to their constituencies and prepare the masses for the coming revolution, and let the Government know that while protesting against the Public Safety and Trade Disputes Bills and the callous murder of Lala Lajpat Rai, on behalf of the helpless Indian masses, we want to emphasize the lesson often repeated by history, that it is easy to kill individuals but you connot kill the ideas. Great empires crumbled while the ideas survived. Bourbons and Czars fell. While the revolution marched ahead triumphantly."

As Prof. Chamanlal very aptly putsv , all the actions of HSRA – from killing Saunders to avenge the ‘National Insult’ of Lala Lajpat Rai’s murder, getting arrested after throwing harmless bombs in the Constituent Assembly, using the weapon of hunger-strike in the jail, converting the Court into a political platform, and finally, approaching the death sentence as planned, denote a very well thought out strategy against the mighty imperialist power, which was left with no choice but to act the way this tiny but intelligent revolutionary group wanted it to. Though the imperial power could successfully liquidate the leading revolutionaries and HSRA physically, the government was defeated morally, politically, intellectually and ideologically.

Bhagat Singh's radicalism - rooted in Punjab's tradition of anti imperial peasant militancy and passed on to him by his uncle Ajit Singh and father Kishen Singh - was increasingly influenced by developments in post-revolution USSR, and the doctrines of nationalism, anarchism and socialism. Hence his political practice had no ideological discomfort with militancy in the pursuit of freedom. Therefore, when most senior leaders of the country had only one immediate goal - the attainment of freedom, Bhagat Singh, hardly out of his teens, had the foresight to look beyond the immediate. He was no ordinary revolutionary who simply had a passion to die or kill for the cause of freedom. His vision was to establish a classless society and his short life was dedicated to the pursuit of this ideal.

Even while in prison, Singh did not give up on his struggle for equal rights and in fact started a hunger strike demanding better treatment for Indian political prisoners in jails, similar to that of the Europeans. In a jointly addressed letter to the Home Member, Government of India, Dutt and Singh demanded :

“A better diet, the standard of which should at least be the same as that of European prisoners. We shall not be forced to do any hard and undignified lobours at all. All books, other than those proscribed, alongwith writing materials, should be allowed to us without any restriction. At least one standard daily paper should be supplied to every political prisoner. Political prisoners should have a special ward of their own in every jail, provided with all necessities as those of the europeans. And all the political prisoners in one jail must be kept together in that ward. Toilet necessities should be supplied. Better clothing.”

The immense popularity of Bhagat Singh and his comrades during their 72-days-long jail hunger strike exposed the political machinations behind attempts to criminalise their activities and posit them as immoral. Its political impact animated the colonial state of exception as the state resorted to force-feeding and other extreme acts of torture in jail, and handcuffed the convicts during their trial in court. The aforementioned letter also brings to light –

“They (the Jail Authorities) handle us very roughly while feeding us artificially, and Bhagat Singh was lying quite senseless on the 10th June, 1929, for about 15 mts., after the forcible feeding, which we request to be stopped without any further delay.”

Jinnah, who was present in the assembly during the bombing, also came out in support of Singh and his associates during their hunger-strike and said:

“You know perfectly well that these men are determined to die. It is not a joke. I ask the hon’ble law member to realise that it is not everybody who can go on starving himself to death. ... The man who goes on hunger-strike has a soul. He is moved by that soul and believes in the justice of his cause; he is not an ordinary criminal who is guilty of cold-blooded, sordid, wicked crime.

Mind you, sir, you cannot, when you have three hundred and odd millions of people, prevent such crimes being committed, however much you deplore them and however much you may say that they are misguided. It is the system, this damnable system of government, which is resented by the people.”

Furthermore, in addition to the harsh treatment meted out to the prisoners, the colonial government shed all semblance of its discourse of the rule of law when the Governor-General exercised his emergency powers (Section 72, Government of India Act 1919) to stop the Lahore Conspiracy Case trial mid-way on 1 May 1930, and by an ordinance, constituted a special three-member tribunal, which had a life of six months. It was bound to sentence the accused within this time limit. The constitution of the tribunal withdrew all rights of appeal and conferred extraordinary powers to dispense with the presence of the accused during trial; a measure that was resorted to on the fourteenth day of its proceedings. Justice Agha Haider, a tribunal member who attempted to maintain some semblance of legality during trial, was removed mid-way through the the trial because he did not follow their line. Justice Haider held, “I am a judge, not a butcher.”

In his own statements before the court, Bhagat Singh continued to oppose the colonial notion of criminality and legality and emphasised on the importance of motive. He argues that the intent of the crime should be the main consideration taken into account when judging the offence of an accused and says –

“The basic principles of the law declare that ‘the law is for man and not man for the law.’ As such, why the same norms are not being applied to us also? Are we being deprived of the ordinary advantage of the law because our offence is against the government, or because our action has a political importance?

My Lords, under these circumstances, please permit us to assert that a government which seeks shelter behind such mean methods has no right to exist. If the law does not see the motive there can be no justice, nor can there be stable peace.”

It is interesting to note that the Viceroy, Lord Irwin, implicitly attested to Singh’s remarks. In a Statement read by Mr. Asaf Ali in court on June 6th, 1929, on behalf of Bhagat Singh and B.K. Dutt, Singh appreciates Irwin’s acknowledgement and says:

“When we were told by some of the police officers, who visited us in jail that Lord Irwin in his address to the joint session of the two houses described the event as an attack directed against no individual but against an institution itself, we readily recognized that the true significance of the incident had been correctly appreciated.”

He further justifies the intent of his crime while also expressing his high regard for human life in the statement when he goes on to say:

“We are next to none in our love for humanity. Far from having any malice against any individual, we hold human life sacred beyond words. Force when aggressively applied is "violence" and is, therefore, morally unjustifiable, but when it is used in the furtherance of a legitimate cause, it has its moral justification. The elimination of force at all costs is Utopian.”

Having eventually been sentenced to death, and even with death waiting for them right around the corner, Singh and his comrades Sukhdev and Rajguru unflinchingly argued their cause and stated that their crime was against the state and not an individual, and therefore claimed that they should be treated as war prisoners. Thus, they demanded that their death sentence be carried out not by hanging, but by a firing squad, like that of War Prisoners. It was with this request that the three comrades addressed the following letter to the Governor of Punjab titled - ‘No Hanging, Please Shoot Us’ and wrote:

“...The main charge against us was having waged war against HM King George, the King of England. Let us declare that the state of war does exist and shall exist so long as the Indian toiling masses and their natural resources are being exploited by a handful of parasites. They may be purely British capitalists or mixed British and Indian, or even purely Indian. They may be carrying on their insidious exploitation through mixed or even purely Indian bureaucratic apparatus. According to the verdict of your court we had waged war and we are therefore war prisoners. And we claim to be treated as such, i.e. we claim to be shot dead instead of being hanged.”

His words ring true in the current socio-political scenario as after almost a century of becoming Independent of British Rule, the ‘Indian toiling masses and their natural resources’ continue being exploited by a ‘purely Indian bureaucratic apparatus’. It is therefore, not surprising that laws like Sedition, and UAPA have resurfaced on the political scenario and terms like ‘terrorists’, ‘conspiracy’ and ‘anti-national’ are used widely in response to any resistance against the state. As such, when there is a state-endorsed blurring of the lines of distinction between crime and resistance, the writings of Bhagat Singh and his comrades become all the more relevant, especially in tracing these developments back to when the colonial fictions of law and juridical norm had a precarious existence; and the myth of ‘order’ were continuously put to test by groups and individuals, and had to be repeatedly re-established.

Bibliography

Heehs, Peter. Terrorism in India during the Freedom Struggle.

Chamanlal. Bhagat Singh ke Sampoorna Dastavej. Aadhar Prakashan, 2005.

Habib, S.Irfan. Remembering a Radical. India International Centre, 2007.

Comments

Post a Comment